Library History

In 1871 Tomah city leaders began a hundred-volume library assembled through donations of books and magazines by local residents. The ladies Library Association soon took over the operation, but as the collection outgrew several successive locations the city took over again because the volunteer operation was no longer adequate.

In 1911 Ernest Buckley, who was a successful geologist, left the city $12,000 in his will to be used as needed for a park and/or a library. City leaders set aside $7,000 of Buckley's bequest for a library, and requested a grant of $10,000 from the Carnegie Foundation. By 1915 they had received the Carnegie grant had secured the services of Claude and Starck, who were well known in the Midwest for their library designs for small communities.

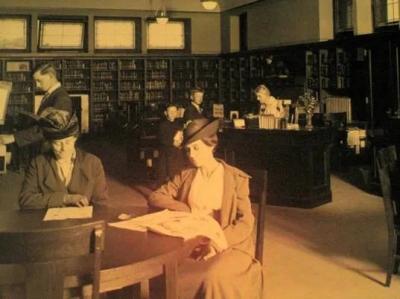

The architects produced the last of the four Wisconsin versions of their "Sullivanesque" design -- a two-story (raised basement and main floor), red brick rectangle topped by a green-tiled hipped roof with overhanging eaves. A buff-color abstract floral design frieze surmounts the walls at the base of the soffit. (The frieze is made of staff, a molded gypsum and fiber material that was manufactured by the American Decorating Company of Chicago.) Rows of windows set within the frieze provided lights from all directions while allowing plenty of wall space for bookshelves. Large windows flanking the entrance vestibule provided additional light to the reading areas on the main floor. The interior represented Claude and Starck's standard, and very functional, library design. The entry led visitors to a mid-level between the basement, which housed community rooms and a classroom, and the main floor, where the library stacks were. The library included a fireplace, built-in bookshelves and magazine racks along the walls, built-in benches, and a desk on the rear facing the main entrance (from where the librarian could easily keep watch over the entire room).

The Tomah library eventually outgrew the Claude and Starck building, and in 1980 an addition designed by the Madison firm of Potter, Lawson, and Pawlowsky, was completed. the flat-roofed, red-brick addition connects to the rear of the original library, allowing Claude and Starck's graceful design to remain the center of attention.

While much of the original woodwork and built-in furniture has been lost in the process of modernization, the original leaded glass windows remain. A portion of the frieze, removed during the 1980 remodeling, is on view in the basement of the library addition.

Article from Frank Lloyd Wright & the Prairie School in Wisconsin: an Architectural Guide by Kristin Visser